Despite Improvements, Veterans Still Need More Medical Marijuana Access

Veterans of the Vietnam War were some of the first to report that smoking marijuana helped them cope with the horrors of war. Their return to the states was marred by the politics and drug war hysteria of the 1970s and marijuana became identified not as a medicine for traumatized soldiers, but the intoxicant of the rebellious, long-haired, anti-American youth. However, some veterans became activists and fought through the “Just Say No” 1980s and the “I didn’t inhale” 1990s to bring awareness of cannabis for victims of trauma.

One such veteran is Michael Krawitz, who served in the Air Force in the early 1980s. He was injured in the line of duty and required thirteen surgeries to recover. At first he worked on medical marijuana issues in his native Virginia, but soon his activism took him all the way to the United Nations, where in 1998 he testified for access to medical cannabis. In 1999, he testified to the National Academy of Sciences Institute of Medicine, which produced a report on marijuana that, among many findings, recommended further investigation into medical cannabis applications.

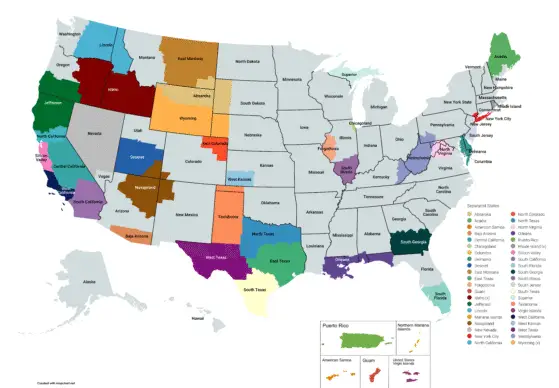

As Krawitz continued his activism into the 2000s, more states were passing medical marijuana laws, but only one (New Mexico) was including post-traumatic stress as a qualifying condition. Many vets, however, were able to qualify for medical marijuana due to other conditions, such as chronic pain. Those vets also reported incredible success with cannabis for managing the post-traumatic stress.

That benefit of medical cannabis may be more than just a treatment; it may be a cure for post-traumatic stress. An associate professor of psychiatry at Yale University, R. Andrew Sewell, believes that the use of cannabis can help the brain form new patterns of thinking to replace the old terrifying patterns suffered by victims of trauma. He explains that the best treatment for post-traumatic stress is “exposure therapy”, where victims recount their traumatic episodes verbally and in writing over a twelve-week course, until the memories are no longer overwhelming. But for some, the memories are too strong. Sewell thinks this may hinge on defects in trauma-sufferers’ CB1 cannabinoid receptor, and studies on mice and apes have shown stimulating the CB1 receptor with the THC from cannabis helps them recover from trauma. Thus, adding a medical cannabis treatment to the exposure therapy improves the success of that therapy. “It’s not like they’d have to keep taking cannabis the rest of their life,” Sewell said. “We’re talking about a cure.”

While veterans using marijuana in most states are criminals under state law, these few states with medical marijuana laws protected veterans for their use. Unfortunately for them, the federal government still considered them criminals if they used cannabis.

Most veterans require medical care from Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals. In certain cases where a veteran requires opioid painkillers, like Oxycontin or Percocet, the VA requires the vet to sign a “pain contract”. There is a problem with the diversion of narcotic prescriptions to the black market and these pain contracts require vets submit urine screens to verify they have been taking their meds, among other requirements. But since the VA is a federal agency, cannabis is not a medicine to them, and when they were finding cannabis in the urine screens, they would consider that a pain contract violation and deny the veteran their painkillers. Essentially, vets were given the choice: painkillers or pot.

That didn’t sit well with Krawitz and the veteran community. A veteran should not have to choose between the best drugs for his pain and the best drug for his post-traumatic stress. Krawitz began lobbying the Veterans Administration to ease the pain contract rules, at least for the veterans in states that had legalized medical cannabis access.

During his fight, Krawitz found other veterans and allies in the medical cannabis community and formed Veterans for Medical Cannabis Access (VMCA) in 2007. Together they continued to work with administrators at the VA until, finally, on January 31, 2011, the VA issued directive 2011-004, “Access to Clinical Programs for Veterans Participating in State-Approved Marijuana Programs”, which proclaimed the following:

[Veterans Health Administration] policy does not administratively prohibit Veterans who participate in State marijuana programs from also participating in VHA substance abuse programs, pain control programs, or other clinical programs where the use of marijuana may be considered inconsistent with treatment goals. While patients participating in State marijuana programs must not be denied VHA services, the decisions to modify treatment plans in those situations need to be made by individual providers in partnership with their patients.

As the New York Times reported, “Doctors may still modify a veteran’s treatment plan if the veteran is using marijuana, or decide not to prescribe pain medicine altogether if there is a risk of a drug interaction. But that decision will be made on a case-by-case basis, not as blanket policy…” Now, veterans in the 20 current medical marijuana states don’t always have to choose between medical cannabis and VA health care, though marijuana is still prohibited in VA hospitals and VA doctors can’t recommend it.

Access for veterans suffering specifically from post-traumatic stress has also improved. In 1996, California became the first medical marijuana state and remains the one with the most inclusive set of qualifying conditions. A doctor can recommend cannabis for any condition he or she believes it will alleviate, including post-traumatic stress.

As other states followed, they resisted California’s “any condition” language and instituted very specific lists of conditions. In trying to prevent people who would “fake it” to get a medical marijuana card, these states refused to add conditions like anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress that require a subjective judgment of illness. Not until 2007 did New Mexico pass a medical marijuana law including post-traumatic stress.

But since the VA directive and along with growing public awareness of returning veterans and their tribulations, three more states (Delaware in 2011, Maine and Oregon in 2013) have amended their medical marijuana laws or passed new ones that recognize post-traumatic stress as a qualifying condition. And, of course, Washington State and Colorado have gone a step further by legalizing marijuana possession and use in 2012 for all adults regardless of medical condition, providing the best access of all.

While these are positive developments, Krawitz and VMCA won’t be satisfied until every vet in every state has access to the cannabis that can improve their mental and physical health. There are still thirty states where a veteran with cannabis is just a criminal pothead. There are still thirteen medical marijuana states where a veteran cannot qualify with post-traumatic stress for medical cannabis or use legalized recreational cannabis.

There are also many other hurdles to clear for veterans seeking medical cannabis. VA doctors are not allowed to write recommendations for federally-illegal cannabis, so vets suffer the additional expense of finding a private physician who will. However, the author of the latest medical marijuana state’s law, Illinois, has filed an amendment to allow veterans being treated for approved conditions by the VA to automatically qualify for the state’s medical marijuana program without another doctor’s recommendation. The bill made it out of committee and awaits a hearing by the full Illinois House of Representatives, approval by the Senate, and a signature from the governor.

Even if a veteran has been able to jump through all the required hoops, they still face discrimination in employment, education, child custody, even organ transplantation. Most medical marijuana states still allow employers to drug test and fire / not hire veterans who fail for marijuana metabolites, even as medical marijuana patients. The federal government still withholds student aid to anyone convicted of a drug offense, which haunts vets who got busted for weed in any state, medical or not. Vindictive spouses have been known to use a veteran’s use of marijuana as evidence against them in child custody hearings and only a handful of medical marijuana states protect against that. And shockingly, veterans in need of life-saving organ transplants have been kicked out of transplant programs when their medical cannabis use becomes known, since most programs will not operate on “known drug addicts”, with only a few of the latest medical marijuana states prohibiting that practice.

This Veterans Day, help Michael Krawitz and VMCA by visiting VeteransForMedicalMarijuana.org and offering your help or donations so that every successive Veterans Day, more and more of our heroes will have access to the cannabis they need. If they can carry a rifle in the sand, they should be allowed a joint in their hand.