Legalization Past, Present, & Future

Marijuana legalization. It’s the hot new trend that’s selling newspapers and getting ratings for cable news networks. Where talk of reforming marijuana laws used to be rare and actually doing so was unheard of, it seems like today you can’t go through a single 24-hour news cycle without hearing of some state pushing for reform, from minimal decriminalization to outright legalization, from CBD-only to whole-plant medical marijuana, and let’s not forget about marijuana’s cousin, industrial hemp.

Yes, it’s a good time to be a loyal HIGH TIMES reader! It seems like nothing can halt the spread of legalization nationwide – it’s inevitable!

Or is it?

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” wrote George Santayana in 1905’s The Life of Reason. It’s sage advice for anyone high on the prospects of nationwide legalization, for there is an older generation of marijuana activists dating back to the founding of this magazine in 1974 who can remember a similar upswing in popular support for marijuana reform, only to see it grind to a halt with the election of President Ronald Reagan and an energized faction of anti-drug parents’ groups.

The current trend of medical marijuana and legalization does seem stronger this time around, but it all hinges on a federal government that is only keeping its hands off thanks to a few memos of guidance and the current administration’s prerogative not to enforce the Controlled Substances Act where states have chosen to reform marijuana laws. A new president enters the White House in 2017, and how he or she prioritizes federal marijuana enforcement could bring legalization to its knees.

The Past

From Colonial Hemp to Cannabis Propaganda

Marijuana prohibition is a rather recent phenomenon. Cannabis had been cultivated in America before it was called America. French explorer Jacques Cartier wrote in the 16th century that the land was “frill of hempe which groweth of itselfe, which is as good as possibly may be scene, and as strong.” In the early 17th century, the American colonists were ordered to grow hemp for the British Empire. By the 18th century, American hemp was prized throughout the world, grown by our first presidents.

But what about psychoactive cannabis, or marijuana? Europeans of the 18th century were engaged in the use of hashish, which had come into vogue thanks to traders from North Africa. It is unclear how much cannabis may have been used for psychoactive purposes in early America, but cannabis as a medicine was common by the latter half of the 19th century. Dr. O’Shaughnessy from Britain had promulgated knowledge of medical cannabis he’d picked up from personal research in India; that information reached America and by the turn of the century, cannabis was exceeded only by opiates and alcohol in patent medicines of the day.

Cannabis as recreation also picked up in the late 1800s. The New York Times was describing cannabis as a “fashionable narcotic” in 1853 and by the 1880s, hashish bars were popular in most large East Coast cities. Also gaining steam in the late 19th century was a counter-movement – the temperance movement – which sought to ban intoxicating liquors. Intoxication was portrayed as anti-family and while it was aimed at liquor it also swept people up in an anti-drug fury as well.

By the 1900s, those fears of intoxication were played upon to usher through a series of laws intended to regulate and control drugs. In order to drum up fear of cannabis, which most Americans knew as either as an industrial crop or a patent medicine, propagandists branded the drug with the Mexican slang term “marijuana”. Soon, state after state passed laws to severely restrict or outright ban marijuana, aided by media portrayals of marijuana as the drug that made Negroes disrespectful to white men and lustful toward white women, made Hispanics lazy or violent, and made teenagers psychotic or suicidal.

From Tax Stamp to “Turn on, Tune in, Drop out”

In 1937, Congress passed the Marihuana Tax Act, making it illegal to possess marijuana unless one had a tax stamp to prove one had paid the federal taxes on it. Additional laws passed in the 1950s added mandatory minimum sentences for marijuana possession. Despite these laws, however, popular use of marijuana began to increase, promoted first by the Beat Poets of the 1950s and early 1960s, followed by the hippies and returning Vietnam vets of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Despite the Tax Act, however, there came a time when US farmers were called to grow industrial hemp. Even though hemp, too, was subject to the tax, it was ignored in what was called the “Hemp for Victory” campaign. In World War II, the Japanese had cut off American supplies of hemp from the Philippines, leading the government to produce a 14-minute video exhorting farmers to grow hemp for the war effort. The program officially ran from 1942-1945, but hemp continued to be grown on some farms until as late as 1957.

Harvard professor Dr. Timothy Leary, known popularly as the LSD guru who advised young people to “turn on, tune in, drop out” in 1967, recognized a fatal flaw in the Marihuana Tax Act. In order to pay the tax to get the tax stamp, one had to bring in their marijuana to be weighed by the authorities. But once one brought in the marijuana lacking a tax stamp, one was breaking the law. Thus, in order to follow the law, one had to break it. In 1969, the US Supreme Court agreed that was a requirement for self-incrimination that was specifically unconstitutional under the 5th Amendment, and for a brief time, marijuana was not federally illegal, though it wasn’t explicitly legal, either, and still banned at the state level nationwide.

Congress and President Nixon reacted quickly by ushering through the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. Rather than basing the prohibition on acquisition of a tax stamp, the CSA relied on the federal power under the constitution’s Commerce Clause to regulate the national market for drugs. By “regulate”, in the case of the drugs like LSD, heroin, and cannabis found in its Schedule I, the federal government meant “ban”, as the drugs in that category are expressly illegal for almost any purpose but very-strictly regulated research that was almost never allowed.

From Drug War to “Just Say No”

With President Nixon, drug policy became a political cudgel with which to beat back progressive political enemies. In 1971, Nixon announced a “total war on public enemy number one, the problem of dangerous drugs in America.” The Drug Enforcement Administration was formed and from its beginnings it placed a high priority on cannabis eradication. Marijuana arrests skyrocketed, used as a tool to oppress mostly minorities, young people, and those opposed to Nixon’s foreign policy.

In spite of, or perhaps because of Nixon’s drug war, marijuana use skyrocketed as well. As Nixon was resigning in ignominy over Watergate, marijuana was reaching into popular culture and support for legalization in public opinion polls was gaining steam. In 1975, an unknown governor of Georgia was running for president, promising to decriminalize marijuana on the federal level, following the lead of states like Oregon and California that had ended arrests for simple possession. In 1977, President Carter was calling on Congress to decriminalize possession of an ounce of marijuana. By 1978, polls that had shown support for marijuana legalization at a scant 12 percent just nine years earlier had risen to 30 percent support nationwide. Many reformers at the time believed that national decriminalization was just over the horizon.

But the pendulum of social approval swung back hard to disapproval. President Carter’s drug advisor, Peter Bourne, was caught up in a prescription drug scandal that surfaced from investigations into allegations Bourne had been partaking of cocaine at a NORML party in Washington DC. Parents groups began to form, a modern temperance movement that again portrayed intoxication as anti-family, with concerned mothers on television holding up gas mask bongs and decrying a society that found up to 60 percent of high school seniors in 1979 having tried marijuana, according to federal surveys.

The revolt against the societal degradation perceived from losing the Vietnam War, a president resigning in scandal, the social upheavals of civil rights battles for minorities and women, and the failed economy and foreign policies of the late 1970s set the stage for a master culture warrior, Ronald Reagan, to become president. Reagan promised “morning in America”, a vision of a new, morally-righteous, tough-on-crime nation, and drugs quickly became a symbol to scapegoat everything Americans rejected about the 1970s. His First Lady, Nancy Reagan, made fighting youth drug use her personal project, and the simplistic “Just Say No” campaign was born.

Marijuana itself wasn’t so much demonized as it was guilty by association with other drugs, namely cocaine. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, cocaine was seen as just another party drug like marijuana; in fact, the covers and centerfolds of this magazine in that era occasionally featured attractive women and lines of coke alongside the trademark photos of marijuana buds. When cocaine and later, crack, were devastating lives and destroying neighborhoods, they took marijuana’s support down with them.

By the late 1980s, Democratic House Speaker Tip O’Neill and Senator Joe Biden were helping pass the instruments of marijuana oppression that survive to this day, like mandatory minimum sentencing and the creation of the Drug Czar’s office. Marijuana legalization support was down to just 1 in 6 Americans and it looked as if it would never recover.

From Medical Marijuana to Legalization

Meanwhile, in California, a new angle on marijuana legalization was developing – its use as a medicine. There had been some limited success on this front, beginning with Robert Randall in 1976 successfully suing the federal government for the right to use cannabis to treat his glaucoma. A federal program began in 1978 to supply his marijuana and soon, up to thirty patients had been enrolled nationwide.

But on a broader scale, activists like “Brownie Mary” Jane Rathbun and Dennis Peron were supplying marijuana as medicine to cancer patients, and later, AIDS patient in the San Francisco Bay Area, throughout the late 1970s and 1980s. By the 1990s, both had been arrested numerous times, but still continued, along with others, to break the law to help the desperately ill. The City of Oakland passed a law allowing for medical marijuana distribution and Peron took advantage of it, opening the Cannabis Buyers Club.

Peron then joined with other notable activists, attorneys, and physicians in co-authoring Proposition 215, legalizing medical marijuana in California. The federal government was stymied, because constitutionally it can neither compel states to enforce federal marijuana laws nor compel states to enact marijuana prohibitions. If the feds wanted to send DEA to arrest sick people in wheelchairs, that was their prerogative, and every time they did so, public sympathy for the patients made for terrible public relations for the government. Aside from raiding the providers and cultivators of medical marijuana on occasion, the government left the medical marijuana patients alone.

Medical marijuana quickly gained popular support, passing in one state or another almost every election cycle since. Opponents called it a “Trojan horse” for recreational legalization, and those concerns caused each successive medical marijuana law to become more strictly regulated to ensure the law couldn’t be gamed by recreational consumers seeking to avoid prosecution. But it was a “camel’s nose under the tent” in the sense that medical marijuana opened up people’s minds to understand that marijuana wasn’t just some demon party drug and that adults could use it not only without serious detrimental effects but also with some medically beneficial effects.

Throughout the 2000s, numerous attempts were made in Colorado, Alaska, and Nevada to legalize marijuana, but each failed to capture the public’s imagination and all went down to strong defeats. Not until 2010 did a statewide legalization seem poised to win at the ballot box. A California medical marijuana provider named Richard Lee, against the advice of reform organizations that counseled he wait until a presidential election year, sunk $1.5 million of his own money into Proposition 19. That measure was polling in the high-50 percent range and shocked the political establishment that considered marijuana legalization a fringe issue. While it ultimately did not win, it did force then Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger to rush through a landmark marijuana decriminalization bill to dilute the appeal of legalizing possession of one ounce.

Finally, in 2012, two states broke through and passed marijuana legalization. In Colorado, the campaign focused on the message that marijuana is objectively safer than alcohol, so it made no sense to treat its consumers as criminals. In Washington State, the campaign focused on a public safety message that legalization would better focus limited police resources and better protect children from marijuana.

The Present

What Good is The Will of The People?

In 2014, Oregon, Alaska, and Washington DC followed Colorado and Washington State in legalizing marijuana. In Oregon, the campaign emphasized the economic benefits of legalization and the futility of prohibition. In Alaska, legalization was proposed as both an economic engine and a way of providing access to their medical marijuana patients who had never really gotten the dispensary systems they require. In Washington DC, a majority-black city, the campaign focused on the racial injustice of marijuana enforcement.

Despite 2014 being a non-presidential year when progressive voters are fewer, the campaigns notched wins that exceeded expectations. Alaska became the first so-called “red state” to pass legalization, with 52 percent support. Oregon’s legalization passed with 56 percent support, the greatest margin of victory of any of the legal states. Both of these states managed those off-year election victories without including odious compromises like stoned driving limits and home cultivation bans found in Washington, or over-taxation found in both Colorado and Washington, portending potential 2016 victories for ever-more-progressive legalization initiatives.

Washington DC is a special case. As a federal district, all its operations are overseen and controlled by Congress. DC could not pass typical tax-and-regulate marijuana legalization as Congress controls its purse strings, so activists passed what’s known as “grow and give” legalization. Adults can possess two ounces and cultivate six plants, and freely give those to one another, but there can be no buying and selling of marijuana in Washington DC. DC wishes to add market regulations to its legalization scheme, but has been thwarted from doing so by spending prohibitions enacted by drug warriors in Congress.

But DC isn’t the only place where the will of the people is being ignored by politicians. In Oregon, the initiative passed was statutory, not constitutional, and Oregon lacks Washington State’s two-year protection against legislative tampering with initiated laws. As of press time, legislators in Oregon have proposed numerous bills that would alter or abolish major portions of the legalization initiative.

Wither Medical Marijuana?

An ongoing problem with marijuana legalization in the Pacific Northwest is how it impacts medical marijuana. Colorado has avoided most of these issues, thanks to a robust medical regulatory scheme and a legalization rollout that integrated the existing medical marijuana industry.

But in Washington State, rolling out legalization alongside medical marijuana has been a disaster. Washington has never had a very well regulated medical program; it lacks even a statewide patient registry found in every other medical marijuana state but California. Dispensaries had never been legalized, but they exploded into being anyway to serve patient needs through various loopholes and technicalities. While pot shops are strictly regulated, limited in number, and sell marijuana with an effective 40 percent tax markup, dispensaries are unregulated, unlimited, and bear no taxation. Legislators in Olympia are desperate to close the loopholes and regulate the medical industry, with some proposing eliminating medical marijuana altogether.

In Oregon, a somewhat similar situation is playing out. Dispensaries are a little better regulated, but the medical marijuana grows that supply them are not. Legislators in Salem are looking to curtail many of the allowances in the medical marijuana program, believing that access to the new recreational market will suffice for all but the sickest Oregonians. Fueling some legislators’ claims of medical abuses was a recent story of Oregon’s largest medical marijuana garden, which ostensibly is cultivating 624 mature marijuana plants for 104 medical marijuana patients… who all live in California (Oregon is the only medical marijuana state that doesn’t require patients to be state residents.)

The Future

The Next States to Legalize

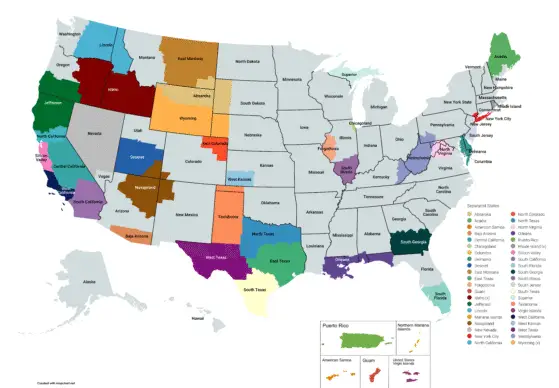

As reform activists have made their forecasts for state legalization, nobody predicted Ohio as a state that would legalize marijuana any time soon, much less before California. But this year, a group called ResponsibleOhio may do just that. The group has invented a novel approach to changing state marijuana laws: funding legalization by enshrining its funders as the state marijuana cartel. Under their plan, any Ohio adult can possess marijuana and grow four of his or her own personal plants if licensed, any adult can open marijuana retail shops and processing facilities, but only the ten investors can operate commercial grows.

California is looked upon as a national game changer in 2016, but whether its disparate marijuana reform factions can come together on one initiative to take to the people remains in question. Currently there are four groups seeking to put legalization on the ballot, with plans ranging from typical tax-and-regulate laws like the other legal states to wide-open treat-it-like-tomatoes legalization.

Nevada reformers have already gotten legalization on the ballot for 2016. Their plan is a tax-and-regulate measure that will allow for possession of one ounce of marijuana, an eighth ounce of concentrates, and the cultivation of six marijuana plants. Commercial growers, processors, and retail stores for marijuana would be created as well.

Other states gearing up for marijuana initiative campaigns are Arizona, Maine, and Massachusetts. Arizona may be the most difficult of the three; medical marijuana barely passed there in 2010 by just 0.13% of the vote and the state has a very conservative streak. However, young libertarian-leaning Republicans are tipping in favor of legalization and may hold the key to an Arizona win. Maine has passed city-wide legalization in Portland and South Portland, but lost a city-wide legalization push in Lewiston, so legalization there hinges on urban voters. Massachusetts has passed reforms in the past two presidential elections by 60 percent or greater, with medical marijuana in 2012 and decriminalization in 2008; chances are good the commonwealth passes legalization in 2016.

And other states may pass legalization through their legislatures just to have some say in how it is done before reformers pass an initiative without the legislature’s input. Lobbyists in Rhode Island, Vermont, and New Mexico believe those states could pass legalization in 2015 or 2016. Hawaii and New Hampshire may follow in 2017. There are also some longshot possibilities in Arkansas and Missouri that may not be such risky bets as a marijuana-filled 2016 political campaign heats up.

When Federal Prohibition Ends

“So when will marijuana be completely legal?” If I had a dollar for every time I’ve heard that question, I could fund a state ballot initiative by myself! It’s a loaded question – what do you mean by “completely” and by “legal”?

If “completely” means “it’s legal to grow, sell, buy, possess, and use marijuana in all fifty states”, then I may not see complete national legalization in my lifetime. Keep in mind that when national alcohol prohibition ended in 1933, Mississippi remained a dry state until 1966, and to this day there are numerous counties, cities, and Indian reservations where alcohol remains prohibited. Certainly, even if the president or attorney general completely removed cannabis from the Controlled Substances Act tomorrow (which, by the way, either could do on signature alone), some state would maintain their marijuana prohibitions for some time to come.

If “legal” means “I can grow and possess as much marijuana as I like and sell it like any other agricultural commodity”, then again, I’m not likely to see that in my lifetime. So long as marijuana’s legalization is connected to its value as a tax revenue enhancement and so long as neighboring states maintain its prohibition, state governments will want to keep as much control over it as possible.

But if the question becomes “when does federal marijuana prohibition end?”, then how soon that happens depends mostly on whether California legalizes and who occupies the White House in 2017. The debate on marijuana will be unavoidable among the 2016 presidential candidates, who are already being pressured on their personal history with marijuana and their views on legalization. Aside from a culture-warrior Republican like a Mike Huckabee or Chris Christie, any potential 2016 presidential winner seeking re-election can’t afford to lose California’s 55 Electoral College votes and the others that have legalized. Young Republicans are increasingly becoming libertarian on the marijuana issue and young Democrats have always massively supported legalization.

I can very easily imagine the next president, in the first term before 2020, using his or her powers to re-schedule marijuana to Schedule III or below to facilitate medical use, or possibly even de-scheduling marijuana altogether and turning the matter over to the states to regulate as they see fit. Unless…

The Nightmare Scenarios

Remember the blowback I described in the late 1970s against the trend of marijuana decriminalization? I can also very easily imagine a scenario where it happens again. America is hit by domestic terrorist attacks, not in major cities, but in heartland America. Investigations uncover that the terrorists have been funding themselves through proceeds of legal marijuana sales, and it’s revealed that the young Americans signed up with these organizations are heavy marijuana consumers. Unscrupulous politicians fan the flames of fear and hatred again and a new wave of anti-marijuana sentiment infects American discourse.

Or constant, heavy use of marijuana concentrates by young people turns out to be more harmful than currently considered. Explosions of butane hash oil manufacture by untrained careless idiots continue to generate awful press coverage. Some little kids eat enough marijuana-infused gummi bears to cause some serious, previously unheard of damage. Teen use of marijuana rapidly increases and some national news program shows damning footage of blazed-out students in some dangerous setting. Adults using legal marijuana misunderstand its interaction with alcohol and cause a massive increase in auto fatalities. As prices fall, use increases and tax revenue decreases, and states that were the first to legalize see budget shortfalls as projected revenues fail to materialize.

At this point, however, I think even my worst nightmare scenarios only slow down the progress of marijuana legalization. It’s hard to imagine anything that could roll back the gains we’ve currently made. Even when the pendulum swung back in the 1980s, the states that decriminalized in the 1970s did not recriminalize marijuana. Only two states have ever increased marijuana prohibition after decreasing it – Alaska recriminalized marijuana in 1990, which was undone by their Supreme Court, and Montana’s legislature repealed medical marijuana in 2011, saved only by the governor’s veto pen.

It’s All Up to You

So how will legalization proceed? Really, it’s up to you. Contact your politicians, from your local city councilman, to your county commissioner, to your state representative, to your congressperson and senators and all the way up to the president. Join together with like-minded legalization supporters in reform groups like NORML and others. Talk to your friends, family, and co-workers about ending adult marijuana prohibition. It may sound corny to think one person can make a difference, but every bit of progress on legalization was made up of the efforts of individuals who share your belief in personal freedom. Legalization is yours, eventually, if you work hard enough for it.