Medical Marijuana Mom Beats State in Court, Wins Back Daughter

Yesterday in Oregon’s Malheur County Courthouse, a young single mother who uses medical marijuana to help treat psychiatric conditions convinced a judge she was neither too mentally ill nor abusing drugs, thereby winning back custody of her one-year-old daughter after ten weeks apart.

It was a verdict few court observers, including myself, expected. (All quotes approximate, as recording was not allowed in the courtroom and I can’t write fast.)

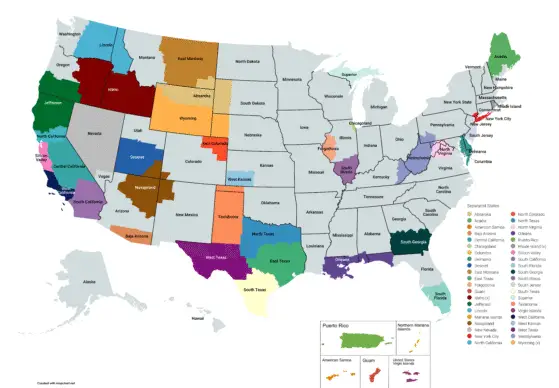

The case began back in October. The scene is Vale, Oregon, a tiny farming community just a few miles from Oregon’s eastern border with Idaho in Malheur County.

Politically, geographically, religiously, and culturally, Malheur County might as well be an extension of conservative, pot-hating Idaho. This portion of the county containing the county courthouse and sheriff’s department is even within that small protuberance of Mountain Time Zone that Oregon shares with Idaho, where you must set your clock back thirty years.

Even though medical marijuana has been legal in the state since 1998, law enforcement in Malheur County has never really accepted the will of the people. In 2014, when Oregon legalized marijuana by a 56 percent vote, Malheur County rejected the Measure 91 by a vote of 68.7 percent against, the greatest opposition to legalization in the state.

So, when a young man named Cody became a registered medical marijuana grower and harvested the 12 cannabis plants he was growing for other patients and his girlfriend, a patient named Katrina, the Malheur County Sheriff’s Office was none too pleased. Maybe it was the fact that his home grow is literally two blocks from the Sheriff’s Department and the County Jail?

Cody, not fully understanding that transparency with police just makes it easier for them to build a case against him, explained how he is a legal, registered medical marijuana grower in complete compliance with state law, and invited them inside his home to see that nothing illegal was going on.

It was then that the cops saw what a grow house can look like when you’re in the middle of a rush to harvest before the weather turns freezing. Curing cannabis was hanging from strings across the ceiling. Nutrients and fertilizers and trimming tools were all about. Piles of garbage and trim had collected throughout the home. Sure, Cody was breaking no laws regarding cannabis, but lo and behold, an unsanitary condition of the home was an immediate and pressing danger to the well-being of Katrina’s little one-year-old daughter, Kaylynn.

Child Protective Services (CPS) arrives at the home. They snap 31 photographs of the condition of the home. Convinced it was an immediate danger to the child, they took Kaylynn from her mother that night, frightened and screaming. During the chaos and terror of kidnapping her child, the CPS workers then convince Katrina to sign a form releasing her mental health medical records to the state. (The kidnapping was captured on Facebook Live by Billy Fisher from the Fight for Lilly Foundation.)

In the passing of ten weeks, Kaylynn is kept in foster care, despite the fact that Katrina had filled out temporary guardianship papers days before the CPS raid that should have transferred custody to one of Kaylynn’s relatives. Malheur County Sheriffs, meanwhile, begin surveilling Cody’s home, driving by in the wee hours of the morning to collect license plate numbers of his visitors.

In one instance, a sheriff’s deputy was traipsing around in Cody’s back yard. When later confronted by Cody, the cop explains that he was investigating his grow, which Cody explained was a futile thing to do in the dead of winter on frozen ground. “Do you plant anything outdoors in the winter?” Cody asks, recording video on Facebook Live at the time. “Do you even understand farming?”

Throughout the encounter, the sheriffs are agitating for Cody to lose his cool, so they can finally have something to bust him for. But he remains calm and asserts his rights, forcing them to eventually leave empty handed.

At trial, about twenty people filled the tiny courtroom to support Katrina and Cody. At the stand were the prosecutor and the blonde CPS worker who kidnapped Kaylynn. Across from them were Katrina, representing herself since she fired her attorney, and the attorney she had fired, who was an appointed guardian ad litem for Kaylynn.

The prosecution’s case hinged on three points of attack. On point (a), the state attempted to portray Katrina a drug addict unable to raise her child. She’d had a lengthy history of mental health issues, for which in the past she’d been prescribed numerous psychotropic medicines. She had moved to Oregon and become a medical marijuana patient for chronic pain conditions; however, she had lapsed on using pharmaceuticals for her mental health and turned to pot. The state hammered home statements from Katrina that pot was “helping to silence the voices in my head that tell me to kill myself and kill others” and that her preference would be to “stay high all day long.”

Katrina’s defense was that she had been on various medications and none of them worked for much longer than a few weeks. She hated the side effects from the drugs and the constant switching of prescriptions in an attempt to find one that lasted. Her use of marijuana is medical for her pain condition and even though Oregon doesn’t recognize marijuana’s medical efficacy for mental health conditions (aside from PTSD), personal use of marijuana is legal anyway. There was no evidence she had any other substance abuse issues or that her marijuana use affected her parenting.

The point (b) attack was the state digging through her lengthy mental health record to paint her as an out-of-control woman wracked by suicidal thoughts, depression, rage control issues, and more. It was embarrassing to listen to the blonde CPS worker on the stand read from an obviously-cut-and-pasted laundry list of every possible symptom she might suffer from her various diagnoses, when few of those were listed as symptoms she’d actually suffered.

Katrina’s defense was Katrina herself. On the stand, she was composed and calm. As a citizen with close to no understanding of courtroom standards, she presented a wonderful case. There were times when the judge had to explain to her how to object, proper questioning of a witness, and what she can’t say from the defense (but could in testimony), and she took each direction well and adjusted perfectly. She explained that she does have some issues, but also mitigates them by having a strong family network (all in the courtroom) that helps take care of Kaylynn when she needs some time to recover.

The point (c) attack came from the 31 photographs the state took of her harvest-ridden home. “It was filthy,” spat the blonde CPS worker. “There was weed everywhere! The smell of dog urine and garbage! Sharp objects and dangerous chemicals within her (Kaylynn’s) reach! The toilet lid was open!” The state took her through each photograph, one by one, for her to explain how everything seen was an imminent danger to the child. The state even questioned family members who reluctantly agreed that the house in that condition was not a safe place for an unsupervised child.

Katrina’s defense was that the house was a mess, but Kaylynn had only been there because babysitting with her grandmother had fallen through. Harvest is a messy, chaotic time and she had tried to keep Kaylynn out of it, and failing that, she had supervised Kaylynn quite closely. In photos from before and after harvest, Katrina established that the home had been kept quite clean and safe.

Katrina also did a great job poking holes in the state’s evocative descriptions of potential danger. “You testified that these sharp picks, trimming scissors, and marijuana were on top of the ferret cage within Kaylynn’s reach,” she asks the CPS worker. “Can you tell me how tall that cage is?” The worker, flustered, said she hadn’t measured how tall it was. When asked how tall the cage came up relative to her own height, she unconvincingly testified that she had no idea. Katrina, a woman at least 5’7″ tall, told the judge that the cage comes up to her chin, prompting a rebuke from the judge about testifying from the defense.

The most damaging blow came when Katrina had noted that the bottles of nutrients and fertilizer in one photograph all seemed to have childproof caps on them. The CPS worker was forced to agree, except in the case of one plastic jug that had a standard screw lid on it. She emphasized that Cody had said that jug was full of fertilizer, that Kaylynn’s toys were scattered around these bottles, and that one-year-olds put everything in their mouths. “Did you test that fertilizer to determine what was in it, that it was actually a potential harm to Kaylynn?” Katrina asked, and no, they had not.

That set the stage for Katrina’s questioning of her boyfriend, Cody, on the stand. “The fertilizer,” Cody explained, “is actually a pro-biotic compound intended to foster good bacteria in the soil that promotes healthy plants.” After explaining the benefits of pro-biotics for a healthy gut and how there are numerous studies showing the efficacy of such compounds in treating gut diseases like Crohn’s, Cody dropped the bomb. “The solution is actually made from a pro-biotic organic honey, fruit juice, and some water.”

Katrina also presented evidence that Kaylynn had been drug tested and came back negative for any controlled substances, including marijuana. Nobody presented any evidence that Kaylynn had ever been harmed or abused. The case closed and the judge retired to make his decision, leaving an anxious family waiting for twenty minutes after three hours of testimony.

The judge returned and did something that activist Serra Frank said she’s not seen in the hundreds of “CPS vs. marijuana moms” cases she’s covered – he essentially returned that little girl to her mom in the courtroom.

“On the point (a) that the mother is suffering from a substance abuse issue, the state has failed to prove its case,” the judge ruled. “On point (b) about the mother’s mental health conditions, the state has failed to prove its case.”

Wow, I thought. This judge just ruled that smoking pot to cope with mental illness was no impediment to good parenting! In Eastern Oregon! In Malheur freakin’ County!

“On point (c) regarding the condition of the home, the state has proved its case,” the judge continued. “However, the defendant has shown that isn’t always the condition of the home. So, CPS, you’re not going to like what I have to say, but you’re going to go over to that home tomorrow at 2pm, and if that home is in a sanitary and safe condition, you will return that child immediately to her mother.”

Usually, nothing brings me more satisfaction than to see cannabiphobic CPS workers losing a quarterly bonus by failing to kidnap another child. Most days, it would be seeing pot-hating redneck cops losing their last hope of eradicating a grow site in their own neighborhood. But yesterday, the sight of an average American family collapsing in each other’s arms weeping tears of joy for the return of their one-year-old daughter / cousin / granddaughter after ten weeks state captivity was the greatest holiday miracle I’ve ever experienced.