Out here in Southern Oregon, I live at the juxtaposition of two state separatist movements.

The State of Jefferson movement began in earnest in the 1940s when the rural, mountainous counties of Southern Oregon and Northern California proposed forming a new state because they felt disconnected and unrepresented by the more liberal and populous parts of their state.

The Greater Idaho movement is a 21st century movement that proposes to move the southern and eastern counties of Oregon into the State of Idaho. Fourteen counties have already approved the idea.

These separatist movements exist all throughout the United States. Some propose to carve themselves new states out of existing ones, like Jefferson. Others propose redrawing existing state borders, like Greater Idaho. Then there are the statehood movements for territories like Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia. In every case, the separatists feel like they are not getting proper representation, whether that be in the form of a rural/urban or geographic/cultural divide.

Amid calls from some to not just separate into new states, but secede as new countries, something Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene called a “national divorce,” it led me to wonder why there isn’t a greater call nationwide to subdivide America into more states? Why shouldn’t states, especially the large western ones, be smaller and more responsive to their respective populations and cultures?

It’s already been done. Western counties of Virginia separated to form West Virginia, for instance. All that must happen, according to the Constitution, is that the legislatures of the affected states and the U.S. Congress must agree to the separation.

Before the Civil War, as the United States were being carved out of the western territories, the issue of slavery dominated the issue of statehood. Would a new state be “free” or “slave?” Our forefathers carved out new states in a delicate balance, so neither side would gain political advantage.

Today, there would be similar federal resistance to carving new states, but in the form of the red/blue Republican/Democrat divide. Creating Jefferson, for instance, creates two new Republican Senators (the area is already represented by a Republican in the House) to nullify the votes of the two Democratic Senators that Oregon would retain. There’d be three new Republican votes in the Electoral College and Oregon would likely lose one. Why would Oregon’s legislature choose to surrender so much political power by approving of Jefferson?

There would also be political resistance at the state level. If the eastern Oregon counties all separated to join Idaho, residents used to no sales tax would suddenly be slapped with a 6 percent Idaho sales tax. Marijuana would instantly become illegal and all the tax revenue and jobs from growing and selling it would disappear. Why would Oregon’s legislature choose to surrender so much economic benefit by approving of Greater Idaho?

These and many other issues make political separatism within the United States seem like a pipe dream. As crazy as a racist rapist felon fraud draft dodger insurrectionist president openly accepting bribes from media companies in exchange for approval of business mergers, or from the mothers of convicted felons in exchange for pardons. As impossible to imagine as an anti-vaxxer in charge of public health, a drunk abuser in charge of the military, a conspiracy theorist in charge of the FBI, a Russian asset in charge of national intelligence, and a puppy murderer in charge of the border.

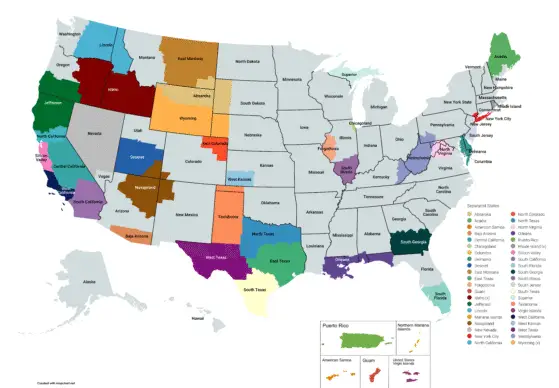

In other words, since nothing is too politically impossible to imagine these days, here’s my imagination run wild on how we get to eighty-five U.S. states through state separatist movements, with links to actual historical attempts to create these new states.

Taxation Without Representation—the D.C. Domino

Following the epic disasters of Trump’s second term, voters sweep Democrats in with trifecta power—control over the House, the Senate, and the Presidency—with power not seen since Barack Obama’s first term, when he had a +78 vote Democratic House, a +16 vote Democratic Senate (which later became filibuster-proof for 72 working days), a +7 percent popular vote mandate, and a 69 percent approval rating.

The president, having learned the lessons of Obama’s failures to wield power, makes statehood for the District of Columbia a major part of the agenda. It easily passes the House and Senate Democrats make statehood admission immune to the filibuster in order to pass the resolution admitting Columbia as the 51st state.

The success of D.C. statehood renews the push in the territory of Puerto Rico. With Columbia adding two more Democratic Senators, there are even more votes to approve of Puerto Rico as the 52nd state, even as Democrats are unsure that the island would be a reliable set of blue votes.

The two new states have swung power toward the Democrats and they retain trifecta power in 2032. This causes Republicans in Texas to activate the unique “Texas Tots” clause in their admission to the Union that allows the state to subdivide into five states without Congressional approval: North, East, South, & West Texas and Texlahoma. The U.S. has 56 states.

Eight new Republican Senators from new Texas states cause Democrats to argue for statehood for the other four U.S. territories—Guam, Mariana Islands, Virgin Islands, and American Samoa—in hopes of gaining Democratic Senators. The second presidential term ends with 60 U.S. states.

The West Fractures

The 2036 Election returns a Democrat to the White House with a Republican House and a 60–60 tie Senate. A citizen initiative to split California into North, Central, South, & West California, Silicon Valley, and Jefferson succeeds. It’s approved by the House and pressure from the ten former-Texas Senators forces the Vice President to break the tie in favor the new states and prevents the President from a veto. The U.S. has 65 states.

With California split into six states, regional separatist movements in the West gain new steam. Southern Oregon’s counties soon join Jefferson, and the eastern counties join Greater Idaho. Eastern Washington and Northern Idaho form Lincoln. New Nevada splits from Las Vegas’s Clark County, now the remaining Nevada. Utah’s southern counties form Deseret. The Navajo Nation of the Four Corners region becomes Navajoland. Arizona’s southernmost counties become Baja Arizona. The U.S. has 70 states.

East Coast Reorganization

With rural areas of the country out west gaining more federal power, citizens in large cities begin clamoring for their own statehood. New York City is the first to cleave from its state, followed by Chicagoland from Illinois. Nantucket & Martha’s Vineyard leave Massachusetts to join Rhode Island, while the Virginia and Maryland counties sharing a peninsula with Delaware reconstitute as Delmarva. The U.S. has 72 states.

Continuing the trend of East Coast metros separating from their states, South Jersey leaves New Jersey, North Virginia is formed, also including parts of West Virginia and Maryland. The rest of West Virginia, along with southwestern Pennsylvania and western Kentucky are restored as Westsylvania. The rural areas of Maine break away from the coast to form Acadia. The U.S. has 75 states.

Splitting the South

The success of bringing on island territories and the Navajo Nation as states greatly increased their ethnic representation in Congress. Seeking similar success for their populations, the southern counties in Georgia form a Black-dominant South Georgia, the southern counties in Florida form a Hispanic-dominant South Florida, and the Cajun counties of Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana Gulf Coast form Orleans. The U.S. has 78 states.

Carving out the Intermountain West

With more ethnic representation, the pendulum swings back to whiter states out west to rebalance the Congress. East Montana separates from its state. Northern Wyoming combines with western South Dakota and southeastern Montana to form Absoroka. Disaffected counties in Nebraska’s panhandle join the remaining Wyoming. The U.S. has 80 states.

Dividing up the Midwest

Carving Chicago out of Illinois leads two other separatist movements to gain traction, creating the new states of South Illinois and Forgottonia. The Upper Peninsula of Michigan is also successful at creating the state of Superior. The U.S. has 83 states.

The last of the historical state separatist movements to come to fruition are the breakaway states of North Colorado and West Kansas, leaving the U.S. with 85 states.